by David Bishop

The month of September has repeatedly proven decisive in Armenian history. Armenian Independence Day on September 21 is quickly approaching. Meanwhile, however, Armenians will reflect with sadness this September on the two-year anniversary of the final genocidal ethnic cleansing of the Artsakh Armenians. Both the war of 2020 and the ethnic cleansing of 2023 were launched in September.

During this tense and uncertain time, with the (perhaps illusory) notion of peace with Azerbaijan being presented to Armenians against the backdrop of capitulation in Artsakh, it is undoubtedly useful to vigilantly maintain the historical record on the atrocities committed against Armenians by Azerbaijan. Within the living memory of many Armenians, we have the Baku pogroms of 1990, which accelerated the displacement and expulsion of the once-large ethnic Armenian community of Baku. But perhaps less well-known is the original Armenian displacement from Baku, which occurred amidst horrifying massacres in September 1918.

The Armenian world of September 1918 was in a time of painful transition. While before the genocide of 1915-16, over 60% of Armenians lived in Ottoman Armenia and only about one third lived in Russian Armenia, now the Ottoman territories were being almost totally wiped out, with desperate survivors fleeing eastward across the old Russian border and into the South Caucasus. Survivors went not only to the struggling territories of the First Armenian Republic, but also to the largest Caucasus cities that long had vibrant Armenian communities, such as Tbilisi and Baku. Though there was no official census in 1918, it is widely estimated that Armenians constituted a full 25% of the population of Baku in 1918, and possibly more as more refugees from the west streamed in.

With the collapse of the Russian Empire from the Bolshevik Revolution, the Russian army’s Caucasus front disintegrated toward the end of World War I, allowing nationalist Turkey to expand its campaign against Armenians even further than the previous Ottoman borders. As Russian forces retreated from the Caucasus to fight the Red Army within Russia, Turkey moved in, invading the Caucasus in 1918 and waging war on the First Armenian Republic, but also on all the other territories of the South Caucasus as the Turks sought to bring the entire region under their control. In this effort, they were supported by ethnic Azeri and Muslim militias springing up on the territory of Azerbaijan. Thus, in the autumn of 1918, a combined Turkish-Azeri force led by Nuri Pasha, the half-brother of the notorious Enver Pasha, moved to seize control of Baku for the Ottoman Empire, raising a large invasion force in Ganja called the “Islamic Army of the Caucasus”.

General Dunsterville (far left) with an Armenian officer and his staff.

By the end of August, the Islamic Army had reached the outskirts of Baku, laying siege to the city. They were resisted by a motley assembly of different forces, including Bolshevik Russian forces loyal to the ethnic Armenian communist leader Stepan Shahumyan, anti-Bolshevik factions, and even a contingent of Allied British forces under the command of General Lionel Dunsterville. The majority of the troops, however, were Armenian fighters of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (the “Dashnaks”). The predominantly Armenian forces held their positions against the numerically superior Turks and Azeris for nearly three weeks until mid-September, inflicting heavy casualties. The presence of Armenian revolutionaries, and their tenacity in combat, further enraged the Islamic Army.

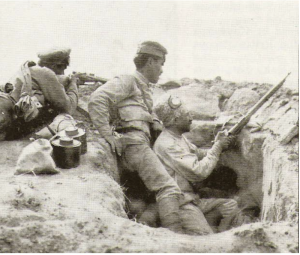

Armenian soldiers of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation firing from an entrenched position in the Battle of Baku, 1918

On September 14, 1918, the Islamic Army broke through the allied defensive lines in Baku, and chaotic fighting erupted throughout the different quarters of the city. Considering the situation hopeless, most allied forces, including the British troops, retreated and abandoned the Armenian revolutionary fighters. This sealed the fate of the city. Soon Baku was under full control of the Islamic Army. Baku’s ethnic Armenian residents, numbering in the tens of thousands, were left to their fate, with many crowding the Baku harbor in the vain hope of evacuation across the Caspian Sea.

The Armenian crowds waiting at the harbor of course could have predicted the genocidal fury that was about to be unleashed upon them. Upon entering the city, the troops loyal to the Ottoman Empire deliberately encouraged ethnic Azeri city residents to loot and plunder their Armenian neighbors’ homes, pushing more displaced people into the streets, where they would soon be massacred. In densely crowded Armenian quarters of the city, it did not take long for the death toll to reach the thousands and tens of thousands when helpless civilians were exposed to armed Islamic Army troops. One British observer recalled:

“In the whole town massacres of the Armenian population and robberies of all non-Muslim peoples were going on. They broke the doors and windows, entered the living quarters, dragged out men, women and children and killed them in the street …. In some spots there were mountains of dead bodies….The most appalling picture was at the entrance to the Treasury Lane from Surukhanskoi Street. The whole street was covered with dead bodies of children not older than nine or ten years.” (Walker, 1980)

Nobody knows with certainty exactly how many Armenians were killed in Baku in September 1918. Different estimates have been given, however, likely the most authoritative source on the Armenian Genocide-era massacres would have to be the Tsitsernakhaberd Armenian Genocide Museum in Yerevan. According to the experts of the Genocide Museum in Yerevan, no less than 29,063 Armenian deaths have been confirmed, with other victims likely, especially as other Armenians were captured and sent to forced labor camps (a signature crime of the Armenian Genocide). This event alone radically decreased the population of Armenians in Baku, as nearly a third were wiped out and many others fled. It would take decades of Soviet rule for the Armenian community in Baku to be restored, though this too would later be destroyed. The tragedy of the Armenian people continues even to this day.